Written by Whitney Clavin

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Pasadena, CA – The fantasy creations of the “Star Wars” universe are strikingly similar to real planets in our own Milky Way galaxy. A super Earth in deep freeze? Think ice-planet “Hoth.” And that distant world with double sunsets can’t help but summon thoughts of sandy “Tatooine.”

Pasadena, CA – The fantasy creations of the “Star Wars” universe are strikingly similar to real planets in our own Milky Way galaxy. A super Earth in deep freeze? Think ice-planet “Hoth.” And that distant world with double sunsets can’t help but summon thoughts of sandy “Tatooine.”

No indications of life have yet been detected on any of the nearly 2,000 scientifically confirmed exoplanets, so we don’t know if any of them are inhabited by Wookiees or mynocks, or play host to exotic alien bar scenes (or even bacteria, for that matter).

Still, a quick spin around the real exoplanet universe offers tantalizing similarities to several Star Wars counterparts.

A more ancient Earth?

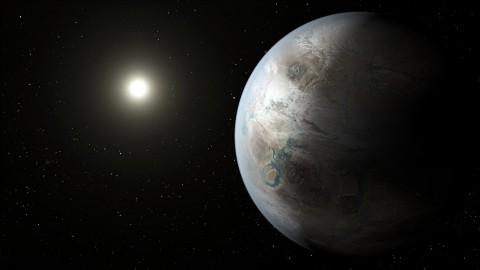

The most recently revealed exoplanet possessing Earth-like properties, Kepler-452b, might make a good stand-in for Coruscant — the high-tech world seen in several Star Wars films whose surface is encased in a single, globe-spanning city. Kepler-452b belongs to a star system 1.5 billion years older than Earth’s. That would give any technologically adept species more than a billion-year jump ahead of us.

The denizens of Coruscant not only have an entirely engineered planetary surface, but an engineered climate as well. On Kepler-452b, conditions are growing markedly warmer as its star’s energy output increases, a symptom of advanced age. If this planet (which is 1.6 times the size of Earth) were truly Earth-like, and if technological life forms were present, some climate engineering might be needed there as well.

City in the sky

Mining the atmospheres of giant gas planets is a staple of science fiction. NASA, too, has examined the question, and found that gases such as helium-3 and hydrogen could be extracted from the atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune. Gas giants of all stripes populate the real exoplanet universe; in “The Empire Strikes Back,” a gas giant called Bespin is home to a “Cloud City” actively involved in atmospheric mining. The toadstool-shaped city provides apparent refuge for a fleeing Princess Leia and company — at least until Darth Vader wreaks his usual havoc.

Many of the gas giants found so far by instruments such as NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope are so-called “hot Jupiters” — star-hugging behemoths far too thoroughly barbecued to be proper sites for floating cities. One recent discovery, however, shows that gas “exogiants” can orbit their stars at distances remarkably similar to those in our solar system.

An international astronomical team discovered a twin of our own Jupiter, orbiting its star at about the same distance as Jupiter is from the sun. The star, HIP 11915, is about the same age and composition as our sun, raising the possibility that its entire planetary system might be similar to ours. This not-so-hot Jupiter, about 186 light-years away from Earth, was detected using the 11.8-foot (3.6-meter) telescope at La Silla Observatory in Chile.

Astronomers using K2, the second planet-finding mission of the Kepler space telescope, recently detected three such planets orbiting a nearby dwarf star. The starlight shining through the atmospheres of these planets could reveal their composition in future observations.

Turn up the heat

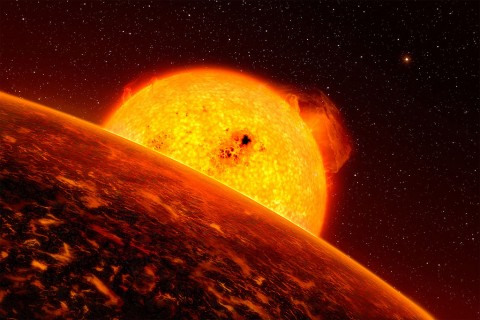

The planet Mustafar, scene of an epic duel between Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker in “Revenge of the Sith,” has a number of exoplanet counterparts. These molten, lava-covered worlds, such as Kepler-10b and Kepler-78b, are rocky planets in Earth’s size range whose surfaces could well be perpetual infernos. Kepler-78b, roughly 20 percent larger than Earth, weighs in at twice Earth’s mass; a comparable density means it could be composed of rock and iron.

That might make it, like Mustafar, suitable for mining, although its extremely tight orbit around its sun-like star, along with scorching temperatures, provides an unlikely arena for industrial operations — or for fencing with lightsabers.

Kepler-10b isn’t much more pleasant. The first rocky world discovered using the Kepler telescope, it also hugs its sun, some 20 times closer than Mercury orbits ours. A balmy day on Kepler-10b means daytime highs of more than 2,500 Fahrenheit (1,371 Celsius), even hotter than lava flowing on Earth. The surface, free of any kind of atmosphere, might be boiling with iron and silicates.

At 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,982 Celsius), however, CoRoT-7b has Kepler-10b beat. This well-grilled planet, discovered in 2010 with France’s CoRoT satellite, lies some 480 light-years away, and has a diameter 70 percent larger than Earth’s, with nearly five times the mass. Possibly the boiled-down remnant of a Saturn-sized planet, its orbit is so tight that its star looms much larger in its sky than our sun appears to us, keeping its sun-facing surface molten.

Deep freeze

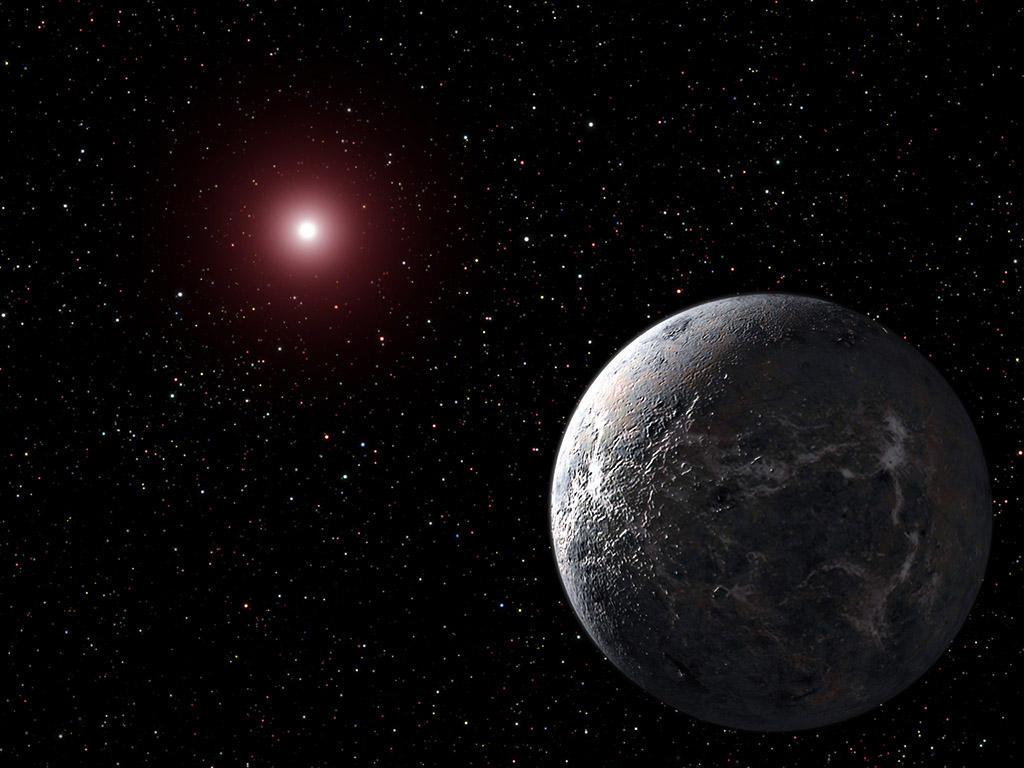

The planet OGLE-2005-BLG-390, nicknamed “Hoth,” is a cold super-Earth that might be a failed Jupiter. Unable to grow large enough, it had to settle for a mass five times that of Earth and a surface locked in the deepest of deep freezes, with a surface temperature estimated at minus 364 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 220 Celsius). That most likely means no “Hoth”-style tauntauns to ride, or even formidably fanged abominable snowmen (aka “wampas”).

Astronomers used an extraordinary planet-finding technique known as microlensing to find this world in 2005, one of the early demonstrations of this technique’s ability to reveal exoplanets. In microlensing, backlight from a distant star is used to reveal planets around a star closer to us.

We won’t have to travel 20,000 light years, however, to visit icy worlds. Saturn’s smoggy moon, Titan, where the Cassini spacecraft’s Huygens probe landed in 2005, is pocked with methane lakes and socked in permanently with thick, hydrocarbon haze. The freeze is so deep that water ice is no different from rock.

Another Saturn moon, Enceladus, looks like a snowball but harbors a subsurface ocean much like Jupiter’s moon Europa, another ice ball with a likely ocean underneath. That ocean would be warmed by tidal flexing as the little moon orbits Jupiter.

Sunset? Make it a double

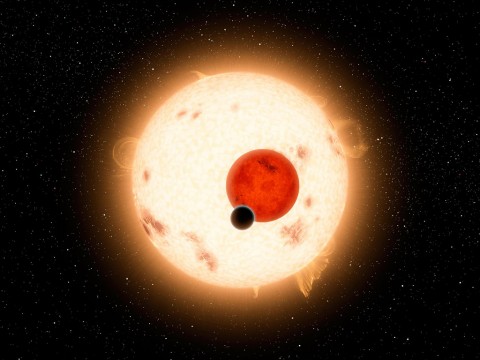

Luke Skywalker’s home planet, Tatooine, is said to possess a harsh, desert environment, swept by sandstorms as it roasts under the glare of twin suns. Real exoplanets in the thrall of two or more suns are even harsher. Kepler-16b was the Kepler telescope’s first discovery of a planet in a “circumbinary” orbit — circling both stars, as opposed to just one, in a double-star system.

This planet, however, is likely cold, about the size of Saturn, and gaseous, though partly composed of rock. It lies outside its two stars’ “habitable zone,” where liquid water could exist. And its stars are cooler than our sun, and probably render the planet lifeless. Of course, we could look on the bright side (so to speak).

When the discovery was announced in 2011, Bill Borucki, the now-retired NASA principal investigator for Kepler at Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California, said finding the new planet might actually broaden the prospects for life in our galaxy. About half of all stars belong to binary systems, so the fact that planets form around these, as well as around single stars, can only increase the odds.

A more recently announced exoplanet, Kepler-453b, is also a circumbinary and a gas giant, though its orbit within its star’s habitable zone means any moons it might have could be hospitable to life. It was the tenth circumbinary planet discovered using the Kepler telescope.

Ocean world

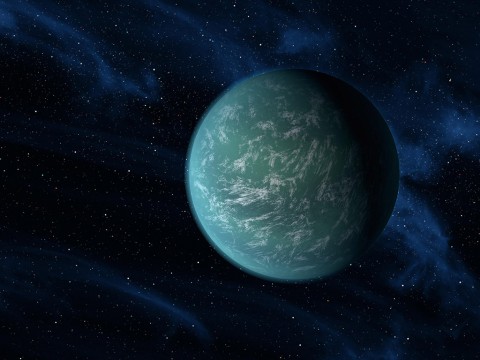

Kepler-22b, analog to the Star Wars planet Kamino (birthplace of the army of clone soldiers)), is a super-Earth that could be covered in a super ocean. Watery, storm-drenched Kamino makes its appearance in “Attack of the Clones.”

The jury is still out on Kepler-22b’s true nature; at 2.4 times Earth’s radius, it might even be gaseous. But if the ocean world idea turns out to be right, we can envision a physically plausible Kamino-like planet, with the help of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. An ocean world tipped on its side — a bit like our solar system’s ice giant, Uranus — turns out to be comfortably habitable based on recent computer modeling.

Researchers found that an exoplanet in Earth’s size range, at a comparable distance from its sun and covered in water, could have an average surface temperature of about 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15.5 degrees Celsius). Because of its radical tilt, its north and south poles would be alternately bathed in sunlight and darkness, for half a year each, as the planet circled its star.

Scientists previously thought such a planet would seesaw between boiling and freezing, rendering it uninhabitable. But the MIT scientists’ three-dimensional model showed that the planet, even with a relatively shallow ocean of about 160 feet (50 meters), would absorb heat during its odd polar summer and release it in winter. That would keep the overall climate mild and spring-like year round.

The shallow depth, by the way, would be ideal for Kamino-style ocean platforms, allowing construction of covered cities at the ocean surface, where armies of clones could march and drill in peace.

Fly me to the exomoon

Endor, the forested realm of the Ewoks, orbits a gas giant and was introduced in “Return of the Jedi.” Detection of exomoons — that is, moons circling distant planets — is still in its infancy for scientists here on Earth. A possible exomoon was observed in 2014 via microlensing. It will remain forever unconfirmed, however, since each microlensing event can be seen only once. If the exomoon is real, it orbits a rogue planet, unattached to a star and wandering freely through space.

More exomoons might soon be popping out from the depths of space. The Harvard-based Hunt for Exomoons with Kepler, or HEK, has begun to scour data from Kepler for signs of them. In early 2015, the researchers examined about 60 Kepler planets and determined that existing technology is sufficient to capture evidence of exomoons.

The hunt could have powerful implications in the search for life beyond Earth. If exomoons are shown to be potentially habitable, it would open another avenue for biology; habitable moons might even outnumber habitable planets. Could they have bustling ecosystems, with life forms even more exotic than Endor’s living teddy bears, swinging between trees Tarzan-style? Stay tuned.

Breaking up is hard to do

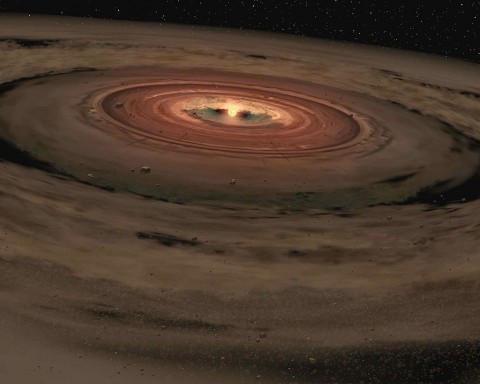

In “A New Hope,” Princess Leia’s home planet, Alderaan, is blown to smithereens by the Empire’s Death Star as she watches in horror. Real exoplanets also can experience extreme destruction. A white dwarf star was caught in the act of devouring the last bits of a small planet in 2015, observed with the help of NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. White dwarfs are super-dense stellar remnants about the size of Earth, but with gravity more than 10,000 times that of our sun’s surface. Tidal forces could rip a planet caught in its pull to shreds.

Observers thought at first they were seeing a black hole in the act of feeding inside a star cluster on the Milky Way’s rim. X-ray observations, however, matched theoretical models of a planet being torn apart by a white dwarf.

A similar observation of a closer white dwarf was made by K2 in 2014. In this case, a tiny rocky object, probably an asteroid, was being vaporized into little more than a dusty ring as it whipped around the star every 4.5 hours.

Our own solar system might once have looked very similar, if anyone was watching.

NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, manages the Kepler and K2 missions for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, managed Kepler mission development. Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. operates the flight system with support from the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Spitzer Space Telescope for NASA.