Written by Kyle Watts

Clarksville, TN – In the late 18th century, brown-iron ore deposits were found on the Western Highland Rim. The Rim is a geographic region in middle Tennessee that extends into western Kentucky and northern Alabama.

Clarksville, TN – In the late 18th century, brown-iron ore deposits were found on the Western Highland Rim. The Rim is a geographic region in middle Tennessee that extends into western Kentucky and northern Alabama.

Iron entrepreneurs from Pennsylvania and New Jersey flocked to middle Tennessee to exploit these iron deposits. One of these men was Montgomery Bell. According to the Tennessee Encyclopedia, Montgomery Bell moved to Dickson County in 1802.

Bell bought James Robertson’s iron works and 640 acres of land and quickly became a legendary figure in middle Tennessee. He helped develop Dickson County’s industry and was appointed a justice of the peace. Bell died in 1855 and donated money that eventually helped create the Montgomery Bell Academy in Nashville. Bell’s legacy, according to the history books, is of a canny entrepreneur who was passionate about quality education for the common man.

However, wealth is never earned alone. It always comes at the cost of someone else. We remember the names of wealthy businessmen, but what about the names of those who built their fortunes?

“King Iron” is a traveling exhibit by the Tennessee African American Historical Group (TAAHG). Funded by Humanities Tennessee, the project tells the story of enslaved iron furnace workers in middle Tennessee.

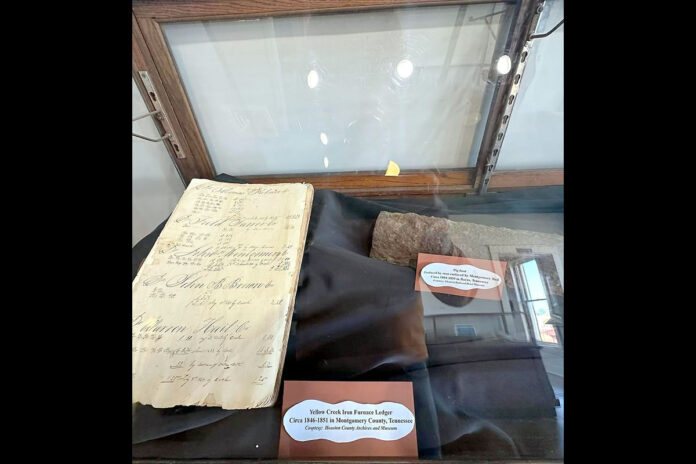

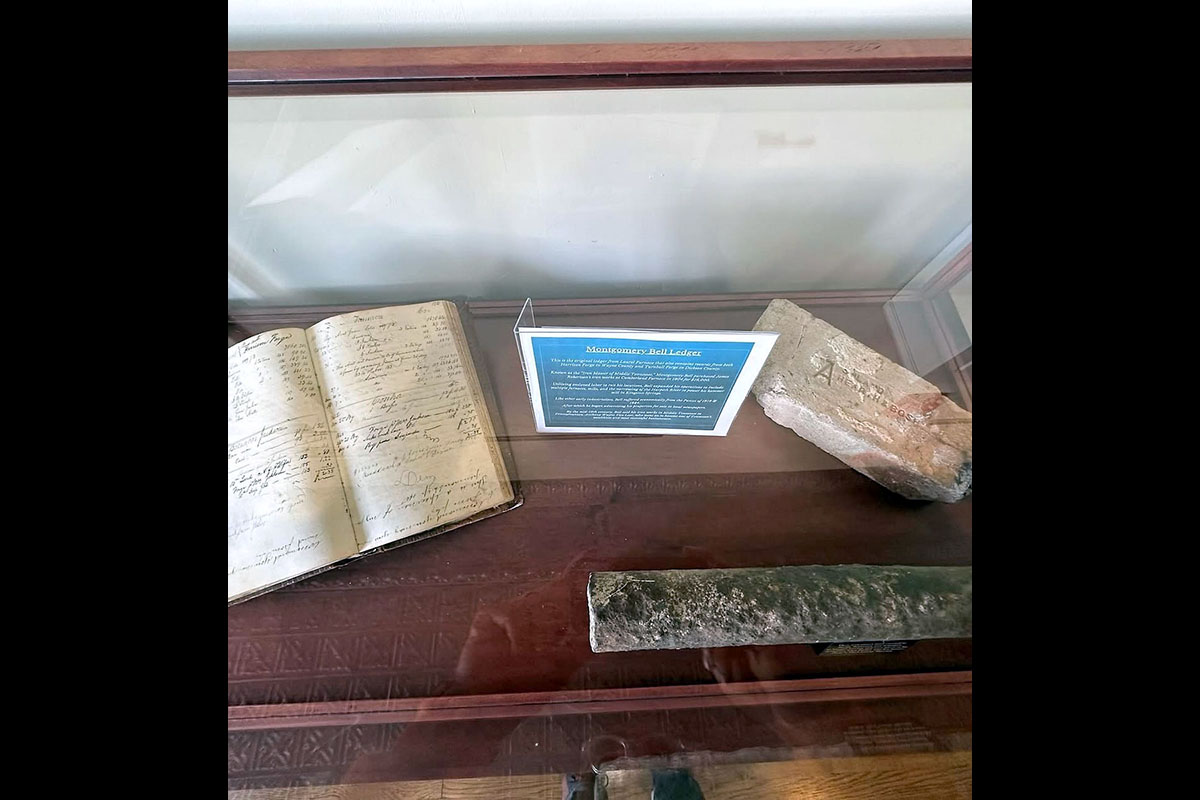

TAAHG president Frederick Murphy and historian Tracy Jepson built the exhibit. It includes artifacts donated by the Cumberland Furnace Museum, the Houston County Archives, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

The artifacts include, but are not limited to, a piece of pig iron produced by men enslaved by Montgomery Bell, ledger books, and goods forged in the 19th century.

“King Iron” also includes a diorama built by retired Customs House Museum Exhibit Preparator Randy Spurgeon. Detailed miniatures depict a limestone furnace operation and the back-breaking skilled labor required to keep the fires burning at around 3,000 degrees fahrenheit 24/7, 365 days a year. Slaves were overworked and constantly at risk of losing life or limb in the name of profit.

“There was no compassion or care for the human rights of the workers,” Jepson said.

Furnaces required anywhere from 100 to 200 slaves to operate. Women worked in support roles – cooking, cleaning, etc. Men could work as quarrymen, colliers, teamsters, guttermen, moulders, firemen, blacksmiths, forgemen, or wood setters.

Working in scorching temperatures, miserable weather conditions, and poor air quality took its toll. Back-breaking labor grinded slaves down physically, and the constant dehumanization by slave masters wore them down mentally.

“A lot of the men didn’t live past fifty years old,” Murphy said.

King Iron is personal to Murphy. His fourth great-grandfather, Ferdinand Jackson, was enslaved at Louisa Furnace in Montgomery County. Jackson was leased from The Forks of Cypress plantation in Florence, Alabama.

Jackson was forced to work six days a week and at least 35 to 40 Sundays per year. Slaves were paid $0.50 for working Sundays. Slaves bought shoes, clothes, and other necessities. It could only be spent at the stores kept by the furnace masters. The money slaves “earned” went right back into the pockets of men like Montgomery Bell.

Jackson had a family while he was enslaved in Clarksville, but they were separated before the onset of the Civil War. Jackson was sent back to The Forks of Cypress, a precautionary move by James and Sarah Jackson, owners of the plantation, to protect their “property.” Ferdinand Jackson and his Clarksville family were never reunited.

“He had to forget that whole life,” Murphy said.

After he was emancipated, Jackson worked at Forks until Sarah Jackson’s death in 1879. He married two more times. He never spoke of the family that was taken from him in Clarksville. “Where do you gain a sense of humanity when you have to be as hard as the steel that you’re making?” Murphy said.

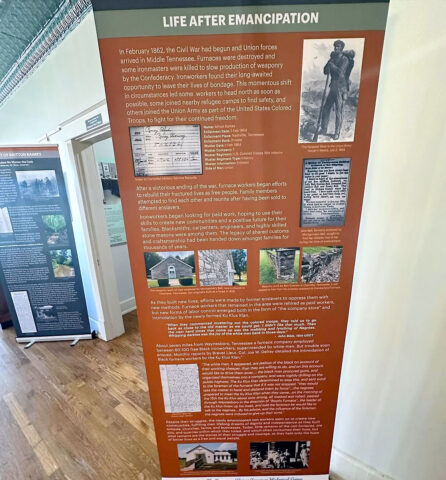

Paranoia was rampant among slave masters in 1856. They were afraid that a Republican president would spell the death of slavery in the South. Democratic nominee James Buchanan defeated Republican John C. Fremont, assuaging the fears of slave owners. At least until Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860. This led to the South seceding from the Union and the outbreak of the Civil War.

This paranoia cost Henry King, a slave in Stewart County, his life. A rumor was spread that furnace slaves were planning an insurrection in 1856. While there was no definitive proof of this, it didn’t stop county officials and slave-masters from making an example of King. King was accused of being the leader of this supposed rebellion. He was beheaded and used as a warning to other slaves.

Four years after the murder of Henry King, the Civil War broke out. Three years after that, the Emancipation Proclamation declared that all enslaved people in the South were free. The proclamation also allowed black men to join the military.

The 101st United States Colored Troops (USCT) has a rich history in Clarksville. The Howard Pettus Home, located where the Dunn Center is now on Austin Peay State University’s campus, housed 1,364 black soldiers. Many of these troops were former iron slaves, including Alfred Ramsey, who enlisted with the 15th infantry in Nashville, TN in 1864.

The “King Iron” exhibit has traveled to Charlotte (TN), Franklin county, and Dickson county so far. Murphy and Jepson have been working hard to bring the exhibit to Clarksville, but there is no firm date for its arrival at this time. The exhibit is currently at Promised Land in Dickson county. Its next stop is Montgomery Bell State Park in spring 2025.

For more information, please visit: www.tnafricanamericanhistoricalgroup.com

Sources

www.tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/montgomery-bell/

www.customshousemuseum.org/news/randy-spurgeon-museum-man/www.theleafchronicle.com/story/news/local/clarksville/2023/06/19/unforgetting-the-forgotten-remembering-the-101st-us-colored-troops/70322417007/