Clarksville, TN – Something amazing is happening at Fort Defiance this summer! A group of men who were integral to the fort’s history are being honored and recognized in a profound way.

Clarksville, TN – Something amazing is happening at Fort Defiance this summer! A group of men who were integral to the fort’s history are being honored and recognized in a profound way.

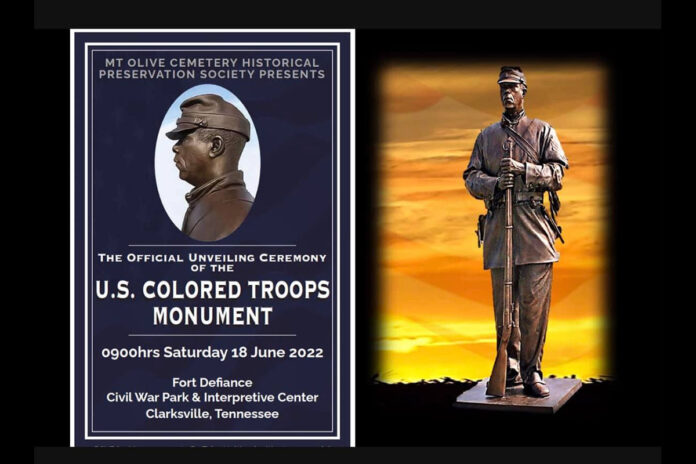

A monument to the men—who were born enslaved and later became soldiers for the Union Army—is being erected in the center of the park. The monument project, whose funding and research have been years in the making, was executed by the Mount Olive Cemetery Preservation Society and approved by the Clarksville City Council.

The perspectives of white people in Clarksville during the Civil War are well documented, as they left behind a myriad of journals and letters. But the formerly enslaved soldiers’ historical voices were silent; I could not find any of their remaining letters or journals for years. It is difficult for the words of a group to be recorded when that group is forced to be illiterate. That forced illiteracy created the problem of their absent voices.

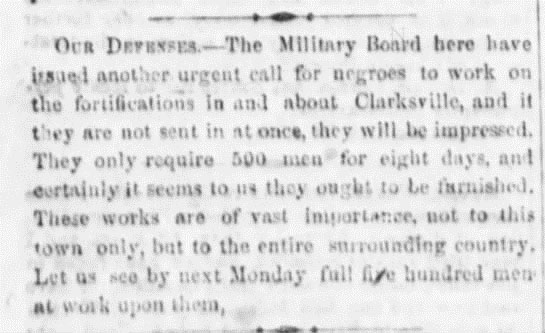

At first, I put their story together as best I could through newspaper clippings and official military records. Those primary sources reveal that Fort Defiance and the surrounding neighborhood are full of African American history and heritage.

In fact, Black hands built the fort we now see perched upon the bluff. It is true that a Confederate engineer designed the fort, but it was the enslaved men who were forced to swing the picks and shovel the dirt to create the earthen walls.

This was an incredibly disrespectful task to be forced upon them. Imagine what these men must have felt and thought as they built something that held the ultimate purpose of keeping them in bondage. This group of men had endured lives full of such disrespect.

Things began to change dramatically, however, in 1863. The Civil War had begun in April 1861, and, at first, the Confederacy benefited from the continued labor of enslaved people in the fields, in Southern homes, in the iron furnaces, in the mines and in almost every type of business throughout the South. Enslaved people were the foundation upon which Southern society was built.

President Abraham Lincoln realized the impact that removing that foundation would have, and he embarked upon a strategy of using this group of millions against the South in the war effort. He had theorized that this shift would likely make all the difference, and he was right.

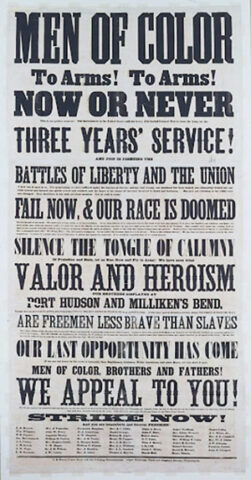

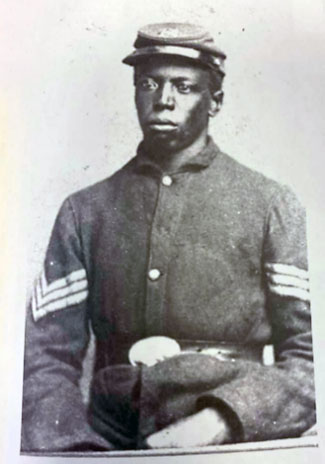

On January 1st, 1863, Lincoln‘s Emancipation Proclamation set everything into motion for the creation of the United States Colored Troops. Then in May 1863, the U.S. War Department issued General Order No. 143, officially establishing the Bureau of Colored Troops. This order resulted in the mustering of the 1st regiment of the United States Colored Troops the next month.

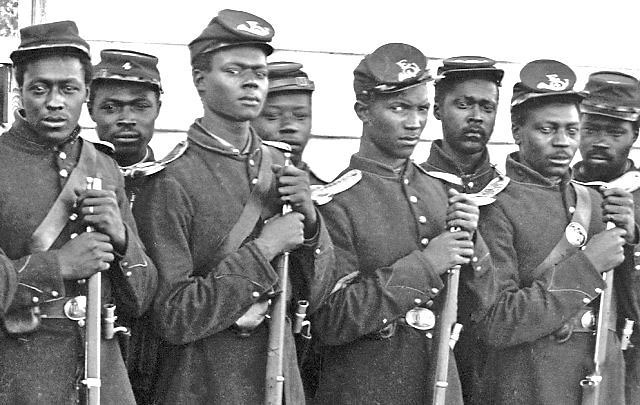

More than 170,000 enslaved men across the South enlisted and transformed themselves from enslaved to soldier. The USCT would ultimately include 135 infantry regiments, six cavalry, 12 heavy artillery and 10 light artillery.

More than 170,000 enslaved men across the South enlisted and transformed themselves from enslaved to soldier. The USCT would ultimately include 135 infantry regiments, six cavalry, 12 heavy artillery and 10 light artillery. Regimental records show that in 1863, thousands of enslaved men in Clarksville and the surrounding countryside made the decision to fight for their freedom.

At the time, approximately half of Montgomery County was enslaved, and Clarksville was a recruiting location—specifically for the 16th and the 101st Infantries. Men from the area also joined the 9th U.S. Heavy Artillery and the 12th, 13th and 17th Infantries.

Fort Defiance itself was the recruiting location for the 16th USCT. Multiple journals and letters of the time confirm this, including the diary of New Providence resident Serepta Jordan and also those of Union soldiers stationed at the fort after its surrender. Confederate men sought to prevent enslaved men from reaching the fort to enlist, but their suppression tactics were ultimately unsuccessful.

“Recruiting goes on slowly at present at Donelson and Clarksville for the reason that just without our lines the rebels keep up a line of patrols to keep the Negroes from coming in. A party of sixty started and only one got through. Although they are watching so diligently about ten per day get through the lines and enlist immediately. When we get two companies armed, we will break the blockade and the men will come in in swarms. It would do you good to see those ragged men come in and put on a suit of US clothes. When they learn they are freemen they stand up their full height.”

The men who joined the USCT in Clarksville played significant roles in constructing railroads and fortifications, defending essential posts and fighting battles at Nashville and Chattanooga.

And through research in recent years, local historian Phyllis Smith and I were surprised to find that some of the words of Clarksville’s USCT do still exist!

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved people kept quiet about their true opinions and kept their stories to themselves out of fear. After the Reconstruction Period, the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws took firm hold in the South. Many things about Black people’s lives in Tennessee became eerily similar to how they’d been before the war. It is well documented that the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee threatened, beat, shot and hanged Black people who tried to vote or assert equality in almost any form.

After the Civil War, many formerly enslaved people kept quiet about their true opinions and kept their stories to themselves out of fear. After the Reconstruction Period, the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws took firm hold in the South. Many things about Black people’s lives in Tennessee became eerily similar to how they’d been before the war. It is well documented that the Ku Klux Klan in Tennessee threatened, beat, shot and hanged Black people who tried to vote or assert equality in almost any form.

Fearing for their lives, many people were unwilling to speak freely about their war experiences or enslavement. But our research discovered that a social worker named Ophelia Egypt collected stories, which were later saved within the Fisk University archives. Ophelia, who was Black, garnered people’s trust and thus preserved their oral histories.

In her collection of interviews, we found the words of at least two men who were USCT soldiers who lived in Montgomery County. Panels that bear excerpts of their stories—their voices echoing over 160 years—will stand next to the USCT soldier statue at Fort Defiance.

Ophelia’s interviews reveal that the men fought for myriad reasons; their words at times are heart-wrenching. Some were terrified of battle but marched on despite their fear, determined to free their mothers and “her little children” from slavery. Some dreamed of a different future for themselves: They wanted to own their own lives, their own bodies, and decide their own futures. They wanted to claim the fruits of their own labor. They could not tolerate seeing their family members sold away from them as possessions, never to see them again. They wanted the right to be educated, and they wanted to protect the women in their life from continual legalized rape.

Below is an excerpt from the story of Joseph Farley. Farley would go on to live in Clarksville after the war. He owned a livery and saloon in town, raised his family in a little house on Brooks Avenue and is now buried in Evergreen Cemetery. He placed great value on education, and his descendants went on to be teachers, principals, nurses and doctors.

“I was a slave way back in 1856…they were mighty hard on colored people. They hung two men by the neck right where I was living…back in those days colored people couldn’t leave their homes without a pass from their master and mistress. You couldn’t even go to church; if you did you were caught on the highway by the padderollers and beat up. Back there they bought and sold colored people just like they do horses and mules now. Many husbands, wives, and children were separated then and never met again…. they had contraband camps, and men, women, and children had to be guarded to keep the Rebels from carrying them back to the white folks…. I lay in the woods all day until night. When I got here then I enlisted in the army.”

“I was a slave way back in 1856…they were mighty hard on colored people. They hung two men by the neck right where I was living…back in those days colored people couldn’t leave their homes without a pass from their master and mistress. You couldn’t even go to church; if you did you were caught on the highway by the padderollers and beat up. Back there they bought and sold colored people just like they do horses and mules now. Many husbands, wives, and children were separated then and never met again…. they had contraband camps, and men, women, and children had to be guarded to keep the Rebels from carrying them back to the white folks…. I lay in the woods all day until night. When I got here then I enlisted in the army.”Farley and his fellow veterans tell of standing up to oppression and tyranny long after they were legally freed from slavery. Farley talks about his life after the war and about the Ku Klux Klan in Clarksville. Wherever there was a strong presence of USCT veterans in a community, the KKK was less likely to exert influence. His words illustrate how that dynamic played out:

“It was a long time before everything got quiet after the War. On Franklin Street here I saw once 100 Ku Klux Klans, with long robes and faces covered…They were going down here a piece to hang a man. There were about 600 of us soldiers, so we followed them to protect the man. The Klan knew this and passed on by the house and went back to town and never did bother the man.”

Abraham Lincoln firmly believed that the Civil War would not have been won without the efforts of the United States Colored Troops, and the efforts of the men who served our country in the USCT have garnered much-deserved attention in recent years. They were a deciding factor in the history that has created our present. And now, in Clarksville, we officially honor their service and sacrifice by carrying forth their voices—and by listening to the wisdom within their stories.

On June 18th, Fort Defiance will welcome you to come see the new statue and read the accompanying panels, and to have your own moment to say to these souls of the past: “We see you, we honor you, and we thank you for your service.”

Additional Information

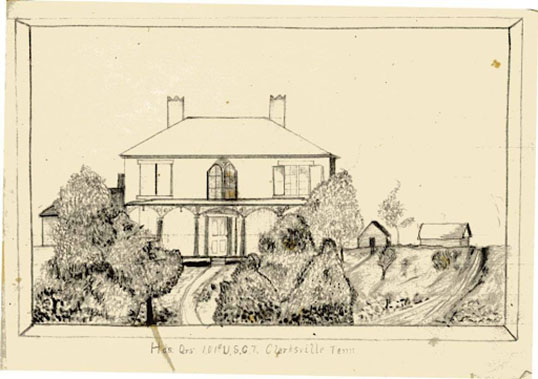

Did you know that the 101st USCT headquarters during the Civil War were in Clarksville? The journal of an officer of that regiment has been preserved, and in it he reveals the location of their headquarters. It sat right where the Dunn Center now sits on the APSU campus!

Recently, the nonprofit Tennessee African American Historical Group has raised the money to place a marker at the location to remember the sacrifice and honor the memory of the 101st USCT in Clarksville. It is scheduled to be erected sometime this year.

www.tnafricanamericanhistoricalgroup.com