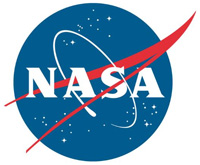

Precise measurements reveal that the exoplanets have remarkably similar densities, which provides clues about their composition.

Pasadena, CA – NASA says the red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 is home to the largest group of roughly Earth-size planets ever found in a single stellar system. Located about 40 light-years away, these seven rocky siblings provide an example of the tremendous variety of planetary systems that likely fill the universe.

Pasadena, CA – NASA says the red dwarf star TRAPPIST-1 is home to the largest group of roughly Earth-size planets ever found in a single stellar system. Located about 40 light-years away, these seven rocky siblings provide an example of the tremendous variety of planetary systems that likely fill the universe.

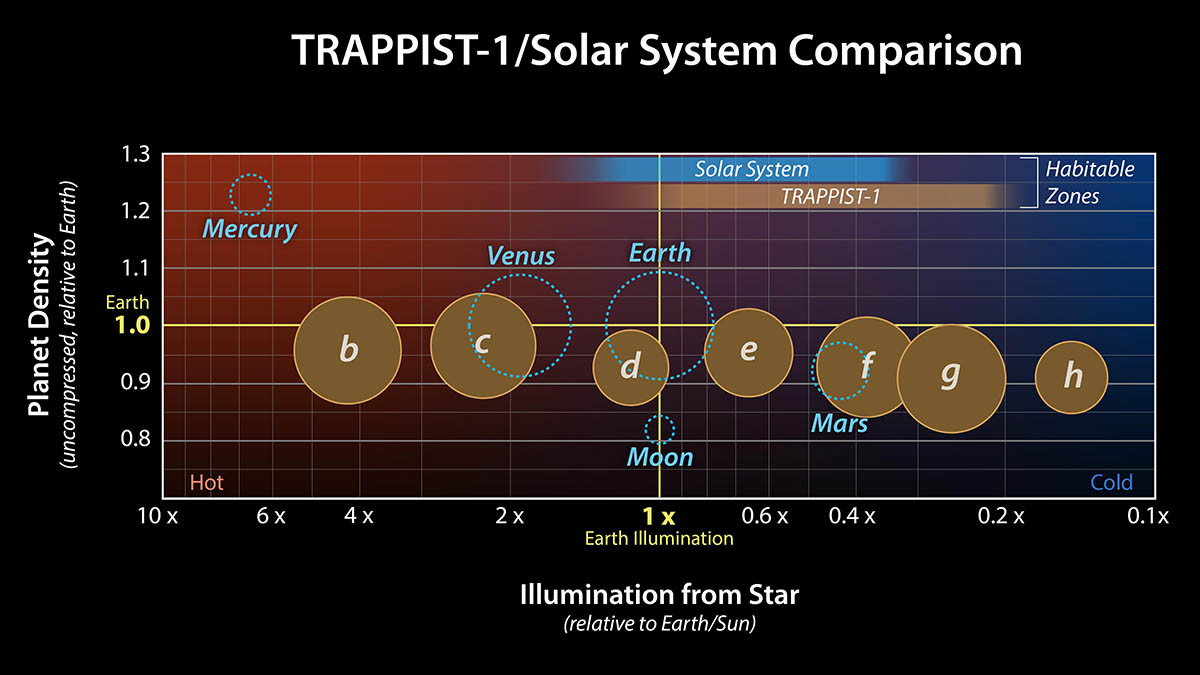

A new study published today in the Planetary Science Journal shows that the TRAPPIST-1 planets have remarkably similar densities. That could mean they all contain about the same ratio of materials thought to compose most rocky planets, like iron, oxygen, magnesium, and silicon.

But if this is the case, that ratio must be notably different than Earth’s: The TRAPPIST-1 planets are about 8% less dense than they would be if they had the same makeup as our home planet.

Based on that conclusion, the paper authors hypothesized a few different mixtures of ingredients could give the TRAPPIST-1 planets the measured density.

Some of these planets have been known since 2016, when scientists announced that they’d found three planets around the TRAPPIST-1 star using the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile.

Subsequent observations by NASA’s now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope, in collaboration with ground-based telescopes, confirmed two of the original planets and discovered five more. Managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, Spitzer observed the system for over 1,000 hours before being decommissioned in January 2020. NASA’s Hubble and now-retired Kepler space telescopes have also studied the system.

Click on this interactive visualization to explore the TRAPPIST-1 planets in their orbit around a small, faint red dwarf star. The full interactive experience is at Eyes on Exoplanets.

All seven TRAPPIST-1 planets, which are so close to their star that they would fit within the orbit of Mercury, were found via the transit method: Scientists can’t see the planets directly (they’re too small and faint relative to the star), so they look for dips in the star’s brightness created when the planets cross in front of it.

Repeated observations of the starlight dips combined with measurements of the timing of the planets’ orbits enabled astronomers to estimate the planets’ masses and diameters, which were in turn used to calculate their densities.

Previous calculations determined that the planets are roughly the size and mass of Earth and thus must also be rocky, or terrestrial – as opposed to gas-dominated, like Jupiter and Saturn. The new paper offers the most precise density measurements yet for any group of exoplanets – planets beyond our solar system.

Iron’s Reign

The more precisely scientists know a planet’s density, the more limits they can place on its composition. Consider that a paperweight might be about the same size as a baseball yet is usually much heavier. Together, width and weight reveal each object’s density, and from there it is possible to infer that the baseball is made of something lighter (string and leather) and the paperweight is made of something heavier (usually glass or metal).

The densities of the eight planets in our own solar system vary widely. The puffy, gas-dominated giants – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune – are larger but much less dense than the four terrestrial worlds because they’re composed mostly of lighter elements like hydrogen and helium.

Even the four terrestrial worlds show some variety in their densities, which are determined by both a planet’s composition and compression due to the gravity of the planet itself. By subtracting the effect of gravity, scientists can calculate what’s known as a planet’s uncompressed density and potentially learn more about a planet’s composition.

The seven TRAPPIST-1 planets possess similar densities – the values differ by no more than 3%. This makes the system quite different from our own. The difference in density between the TRAPPIST-1 planets and Earth and Venus may seem small – about 8% – but it is significant on a planetary scale. For example, one way to explain why the TRAPPIST-1 planets are less dense is that they have a similar composition to Earth, but with a lower percentage of iron – about 21% compared to Earth’s 32%, according to the study.

Alternatively, the iron in the TRAPPIST-1 planets might be infused with high levels of oxygen, forming iron oxide, or rust. The additional oxygen would decrease the planets’ densities. The surface of Mars gets its red tint from iron oxide, but like its three terrestrial siblings, it has a core composed of non-oxidized iron. By contrast, if the lower density of the TRAPPIST-1 planets were caused entirely by oxidized iron, the planets would have to be rusty throughout and could not have solid iron cores.

Eric Agol, an astrophysicist at the University of Washington and lead author of the new study, said the answer might be a combination of the two scenarios – less iron overall and some oxidized iron.

Because they’re positioned too close to their star for water to remain a liquid under most circumstances, the three inner TRAPPIST-1 planets would require hot, dense atmospheres like Venus’, such that water could remain bound to the planet as steam. But Agol says this explanation seems less likely because it would be a coincidence for all seven planets to have just enough water present to have such similar densities.

“The night sky is full of planets, and it’s only been within the last 30 years that we’ve been able to start unraveling their mysteries,” said Caroline Dorn, an astrophysicist at the University of Zurich and a co-author of the paper. “The TRAPPIST-1 system is fascinating because around this one star we can learn about the diversity of rocky planets within a single system. And we can actually learn more about a planet by studying its neighbors as well, so this system is perfect for that.”

JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, managed the Spitzer mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Science operations were conducted at the Spitzer Science Center at IPAC at Caltech. Spitzer’s entire science catalogue is available via the Spitzer data archive, housed at the Infrared Science Archive at IPAC. Spacecraft operations were based at Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado.