Written by Elizabeth Zubritsky

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Greenbelt, MD – How long might a rocky, Mars-like planet be habitable if it were orbiting a red dwarf star? It’s a complex question but one that NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission can help answer.

Greenbelt, MD – How long might a rocky, Mars-like planet be habitable if it were orbiting a red dwarf star? It’s a complex question but one that NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission can help answer.

“The MAVEN mission tells us that Mars lost substantial amounts of its atmosphere over time, changing the planet’s habitability,” said David Brain, a MAVEN co-investigator and a professor at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder. “We can use Mars, a planet that we know a lot about, as a laboratory for studying rocky planets outside our solar system, which we don’t know much about yet.”

At the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union on December 13th, 2017, in New Orleans, Louisiana, Brain described how insights from the MAVEN mission could be applied to the habitability of rocky planets orbiting other stars.

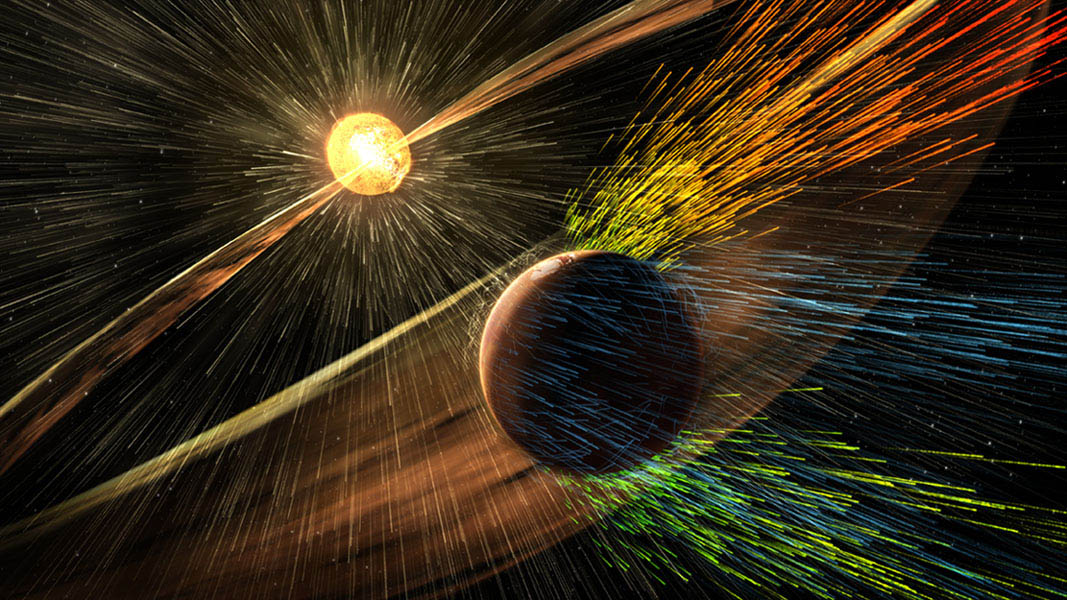

MAVEN carries a suite of instruments that have been measuring Mars’ atmospheric loss since November 2014. The studies indicate that Mars has lost the majority of its atmosphere to space over time through a combination of chemical and physical processes. The spacecraft’s instruments were chosen to determine how much each process contributes to the total escape.

In the past three years, the Sun has gone through periods of higher and lower solar activity, and Mars also has experienced solar storms, solar flares and coronal mass ejections. These varying conditions have given MAVEN the opportunity to observe Mars’ atmospheric escape getting cranked up and dialed down.

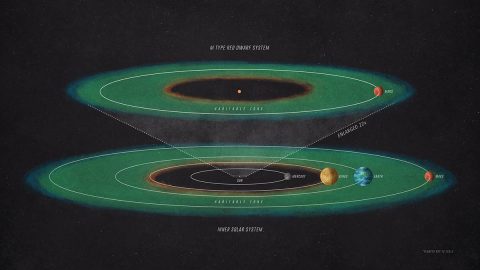

Brain and his colleagues started to think about applying these insights to a hypothetical Mars-like planet in orbit around some type of M-star, or red dwarf, the most common class of stars in our galaxy.

The researchers did some preliminary calculations based on the MAVEN data. As with Mars, they assumed that this planet might be positioned at the edge of the habitable zone of its star. But because a red dwarf is dimmer overall than our Sun, a planet in the habitable zone would have to orbit much closer to its star than Mercury is to the Sun.

That cranks up the amount of energy available to fuel the processes responsible for atmospheric escape. Based on what MAVEN has learned, Brain and colleagues estimated how the individual escape processes would respond to having the UV cranked up.

Their calculations indicate that the planet’s atmosphere could lose 3 to 5 times as many charged particles, a process called ion escape. About 5 to 10 times more neutral particles could be lost through a process called photochemical escape, which happens when UV radiation breaks apart molecules in the upper atmosphere.

Because more charged particles would be created, there also would be more sputtering, another form of atmospheric loss. Sputtering happens when energetic particles are accelerated into the atmosphere and knock molecules around, kicking some of them out into space and sending others crashing into their neighbors, the way a cue ball does in a game of pool.

Finally, the hypothetical planet might experience about the same amount of thermal escape, also called Jeans escape. Thermal escape occurs only for lighter molecules, such as hydrogen. Mars loses its hydrogen by thermal escape at the top of the atmosphere. On the exo-Mars, thermal escape would increase only if the increase in UV radiation were to push more hydrogen to the top of the atmosphere.

Altogether, the estimates suggest that orbiting at the edge of the habitable zone of a quiet M-class star, instead of our Sun, could shorten the habitable period for the planet by a factor of about 5 to 20. For an M-star whose activity is amped up like that of a Tasmanian devil, the habitable period could be cut by a factor of about 1,000 — reducing it to a mere blink of an eye in geological terms. The solar storms alone could zap the planet with radiation bursts thousands of times more intense than the normal activity from our Sun.

However, Brain and his colleagues have considered a particularly challenging situation for habitability by placing Mars around an M-class star.

“Habitability is one of the biggest topics in astronomy, and these estimates demonstrate one way to leverage what we know about Mars and the Sun to help determine the factors that control whether planets in other systems might be suitable for life,” said Bruce Jakosky, MAVEN’s principal investigator at the University of Colorado Boulder.

MAVEN’s principal investigator is based at the University of Colorado’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, Boulder. The university provided two science instruments and leads science operations, as well as education and public outreach, for the mission.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the MAVEN project and provided two science instruments for the mission. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Mars Exploration Program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington.

For more information about MAVEN, visit: