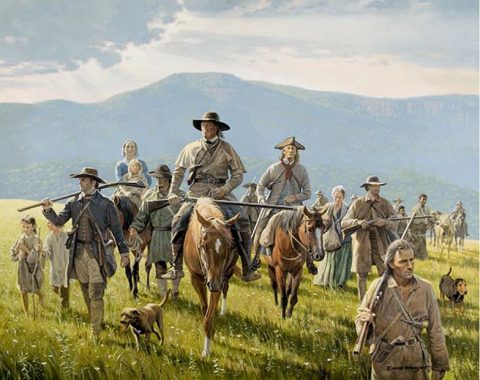

Clarksville, TN – In 1780 a group of 300 daring pioneers decided to journey upon the Tennessee River and the Cumberland River in flatboats and canoes.

Clarksville, TN – In 1780 a group of 300 daring pioneers decided to journey upon the Tennessee River and the Cumberland River in flatboats and canoes.

The destination for some of them would be present day Montgomery County, upon the Red River at the mouth of Passenger Creek. Yet, in order to arrive at their destination they had to guide their boats through a frontier full of Native Americans determined to attack them.

Why would they attempt such an endeavor which seemed to almost promise violence, deprivation, and other hardships?

Henderson intended to establish frontier stations along the Cumberland River from which land surveying and speculation might proceed. The settlers had been promised hundreds of acres of land in recompense for their participation.

During the first part of the journey they had already suffered attack and loss as the Chickamaugans shot at them from the banks of the Tennessee River. The flotilla, led by John Donelson, was then forced to venture through a narrow part of the river they called “the Suck” which in turn made them sitting ducks for the Chickamaugans.

Lives were lost in moments of frenzied terror and possessions sacrificed to the river. Yet, the group continued on, determined to accomplish their goals.

What happened next? Did they beat the odds, arrive at their desired destinations, and receive the promised land along with its hastily promised future? Already they had suffered, but they pressed on, no doubt driven by hopes and dreams despite their circumstances.

Once the flotilla made it through the horrific experience at “the Suck,” the main attack from the Chickamaugans ceased and the flotilla was not pursued. Yet, the danger did not completely end, but simply morphed into a different struggle. By the time the group reached the mouth of the Tennessee River it was March 21st, 1780. John Donelson Jr. reported, “Our provisions were exhausted, and the crews were worn down with hunger and fatigue.” And next they must travel not downstream, but against the current of the Ohio River, and then up the Cumberland.

Upon arriving at the mouth of the Tennessee River, part of the group opted to stay with the current and continued downstream to Natchez and New Orleans on the Mississippi River, calling out farewell until they could no longer be heard.

Yet, through much struggle and determination the rest of the group paddled and poled against the currents of the Ohio and then the Cumberland for weeks. They later told tales of shooting buffalo, bears, and “a delicious swan” to stave off their hunger, along with cooking herbs they found in the Cumberland river bottom, which some called “Shawnee salad”. They reported it to be “a poor dish – just better than nothing”. (John Donelson Jr. 1780)

Then finally, they arrived at the mouth of the Red River, otherwise known as present day Clarksville, Tennessee, on April 12th, 1780 where the group divided again. A portion led by Moses Renfroe took their leave in order to travel up the Red River searching for a suitable settlement location. The rest of the group continued up the Cumberland River towards present day Nashville.

A young man named Armistead Miller was part of the Renfroe party and later relayed, “…about 80 souls and some negroes, went nine miles up Red River, and settled upon the bluff.” The location Armistead spoke of is at the mouth of present day Passenger Creek and was originally called Fort Union.

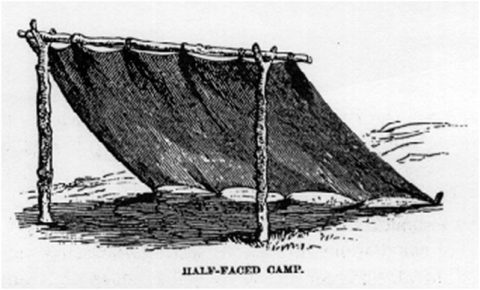

He also shared that the group, “made a fort of half-faced camps two rows from the river, and the ends open. They cut off some bushes, and planted some corn and pumpkins without a fence. They caught sturgeon, one six feet and other fish, and hunted buffalo, elk, bear, deer, ducks, and geese.”

Armistead also reported that one member of their group was attacked by a panther while hunting near the station. It seems there was no shortage of wildlife to either hunt or fear and that the diversity of the wildlife was much greater than what we experience today.

The leader of the settlement, Moses Renfroe, was also known to be a fine gunsmith, and it was said that “a Renfroe rifle was a passport all over the west.” Also, Moses and some of his family members, Jesse and Isaac Renfroe, were all three Baptist preachers.

Apparently, there was little chance the station would be left without spiritual guidance. The influence of the Renfroe family upon the group seemed to be so significant the settlement became known as Renfroe Station rather than Fort Union.

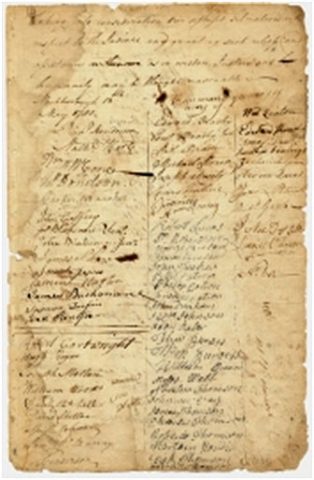

The Cumberland Compact

As the settlers of the various stations spread out across present day middle Tennessee, they attempted to organize themselves. They felt it necessary to create some form of government since they were so far removed from civilization. They created a document called “The Cumberland Compact” which called for the election of 12 representatives or judges from the different stations or forts. One of these representatives was to come from “Fort Union.”

Only white men over the age of 21 could vote for the judges, or serve in the other capacities such as clerks and sheriffs. The document stipulated that all men over the age of 16 must serve in the militia and also provided for needed services such as estate administration, enforcement of the law, and other legal matters.

There was one law in particular, the law against stealing, which was stringently enforced on the frontier. Consequences for stealing in the settlements ranged from capital punishment by hanging or lashes and branding. Yet, though the compact brought some order and security to the settlements, it could not effectively protect the pioneers from their primary threat.

Violence at Renfroe Station

It did not take long for the Native Americans, in this case most likely from the Chickasaw tribe, to become aware of the new settlement on the Red River. The first occurrence of violence perpetrated upon the Renfroe party happened on a Sunday in June 1780, approximately two months after their arrival. The daily lives of the pioneers at that time were concerned with survival as they gathered food and hunted local game, while living in their half-faced camps.

For example, Armistead Miller relayed that in June of that year, “John Lumsden…was in a mulberry tree gathering fruit…Three Shawnees were seen slipping through the bushes, and all fired, killed Lumsden, scalped him, and dogded (sic) off. The whites carried in his body and buried it. The next day, Nathan Turpin, went out hunting, and on his return was killed and scalped within 300 yards of the station. All was now consternation. Men were sent to French Lick, Heaton’s, and Mansker’s for aid to move to those stations.” (Armistead Miller, 1844, Draper Manuscripts)

The settlement had barely existed for two months before the inhabitants decided to abandon it out of fear. Yet, even though the settlers stayed only for a short time, they left behind artifacts and remains along the Red River. Due to the findings of a local relic hunter, the location of the settlement can be approximated near the mouth of Passenger Creek.

Below are some of the belongings the settlers dropped or lost in the dirt almost 240 years ago: coins, buttons, an ink well fragment, part of a pewter spoon, a brass key, brass nails, impacted round balls, gun flint, 50 caliber rifle ball, 70 caliber musket ball, pottery fragments, and a brass shoe buckle. Those who dropped them could have probably not imagined we would value them and find them so interesting.

Also, two old graves were located nearby, but have not been verified. They are likely the graves of Nathan Turpin and John Lumsden.

The Massacre at Sycamore Creek

As the settlers proceeded with the removal of their party to other stations, a guard of 15 or 20 men were sent to escort them. They divided the approximately 80 settlers into two groups. The route used was an existing bison trail or game path that ran south from Port Royal, through Robertson County alongside Millers Creek, then through modern-day Coopertown before crossing Sycamore creek. The first group arrived safely at French Lick, but the second group was not so fortunate.

After the first day of travel the second group decided to camp at a spring that emptied into Sycamore Creek. At this same time, a party of Chickasaw traveling south intercepted the travelers. Consequently, at daybreak of what was to be their second day of travel to the other relatively safe frontier stations, approximately 50 Chickasaw attacked the settlers.

Armistead Miller later shared with an historian what he remembered about that day. “Between daylight and sunrise, Joseph Renfroe and negro, Jessie went to the spring to get water, both were shot down, and then the Indians dashed in and fired upon the camp. One Indian ran up and tomahawked Abraham Jones….old Jacob Johns fought till he shivered his gun to pieces. He was finally killed together with his wife and daughter.”

Hugh Bell relayed, “A sharp battle of some 30 minutes ensued. At the first fire, James and Samuel Hollis ran off to the Bluff at French Lick. A negro who belonged to one of the Turpins fought with distinguished bravery, encouraging his master and the others never to yield while life lasted.”

Another member of the group, Robert Weakley, remembered that “Mrs. Jones escaped with her son, Shadrack, a lad, and an infant daughter, Betsy, in her arms”. She hid underneath a shelving rock with her children hoping that the attackers would not find her or hear her young children. She waited and hid there for an entire day and night when finally a relief party rescued her.

Overall, the attack resulted in 15 deaths among the settlers. The families that survived the attack were then scattered amongst three different stations that were located in or near present day Nashville: French Lick, Mansker’s Station, and Heaton’s Stations.

Conclusion

The violent attacks would continue in the Cumberland region until the end of the 18th century and not all of the pioneers were willing to remain in order to hold onto their land claims. Less than half of the 244 signers of the Cumberland Compact remained. Approximately 40% of the signers were either killed or missing.

This particular station (Renfroe Station) and its story predates another that is well known in Montgomery County, the massacre at Sevier Station (1794). The Sevier Station massacre occurred near the end of two decades of conflict between settlers and Native Americans. Yet, by the time Tennessee became a state in 1796 the area was generally safe from hostilities. Simply put, this was due to the fact that the Native Americans in the area were attacked by militias from Tennessee, Virginia, and Kentucky.